The term PLM for product lifecycle management has been around for around 20 years. Back then, no one talked about digitalization or digital transformation, AI was still a specialty of computer science geeks, and hardly anyone in Germany knew about IoT. Now it’s all there. And PLM is fading into the background. Only in terms of marketing? Or is the topic losing importance? To find out, I’m having a series of conversations with the vendors who have felt comfortable under the big PLM umbrella over the past 20 years. For some, this is worth an exclusive article for which they have a budget. Others are content with input for a summary post, which I’ll put at the end of this little series of articles.

The term PLM for product lifecycle management has been around for around 20 years. Back then, no one talked about digitalization or digital transformation, AI was still a specialty of computer science geeks, and hardly anyone in Germany knew about IoT. Now it’s all there. And PLM is fading into the background. Only in terms of marketing? Or is the topic losing importance? To find out, I’m having a series of conversations with the vendors who have felt comfortable under the big PLM umbrella over the past 20 years. For some, this is worth an exclusive article for which they have a budget. Others are content with input for a summary post, which I’ll put at the end of this little series of articles.

The interesting history of a term

How did it all begin? For a long time, minds argued about that. Many wanted to have invented the new acronym. Prof. Michael Abramovici, then still with the consulting firm Ploenzke and not yet a professor, used the term in the event he organized for Ploenzke on product data management. When for the first time? It is almost impossible to find out. But I can remember another story very well that made the term and its origin seem very reasonable and logical to me at the time.

IBM – around the turn of the millennium still a respected provider of engineering software, the exclusive sales channel of Dassault Systèmes for the CAD/CAM products from Paris, but also manufacturer of its own software for industrial product data management (PDM) – discovered for its own development and production of computer hardware as well as the associated order processing that the PDM system was not sufficient at all to support the core processes in terms of information technology throughout. At that time, there was a press release in which IBM informed the industrial world about an envisaged strategic cooperation, which, in addition to IBM and Dassault Systèmes, also included Ariba and SAP, among others. And what this was intended to do, IBM called Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) in that press release.

How quickly things have moved on, and so very differently than expected. The strategic cooperation of the companies mentioned never came about. The topic disappeared from IBM’s agenda just as suddenly, but less conspicuously, as it had arrived there. And it did not stop at the withdrawal from this partnership. It wasn’t long before IBM sold its own PDM system to Dassault Systèmes, and some years later handed over the entire Engineering Software division, including its staff, to its former closest partner. And even though IBM has re-emerged in the industry in recent years with Watson IoT, the experts, engineers, and technicians today hardly know the company as a provider for their needs anymore.

Dassault Systèmes though was one of the big players in PLM in the following two decades. They first called it 3D-PLM, because they saw the 3D model – of course preferably generated with their own system CATIA – as the central element of digital product data. The other main vendors were PTC and Unigraphics Solutions, which was acquired by Siemens in 2007 and whose NX and Teamcenter systems now form the core of the Siemens Digital Industries Software portfolio. SAP also called a division SAP PLM for a few years, but that didn’t last very long and was aimed primarily at the pharmaceutical and other process industries.

From left: Bernard Charles, CEO Dassault Systèmes, Jim Heppelmann, CEO PTC, Tony Hemmelgarn, CEO Siemens Digital Industries Software, Johann Dornbach, CTO PROCAD (photo PROCAD) and Karl Heinz Zachries, CEO CONTACT Software, (other photos Sendler)

Other industrial software providers such as Autodesk never made the leap to the PLM level, despite multiple attempts and acquisitions, and do not play any role in this context. Still others – and this is especially true in Germany – have dedicated themselves entirely to PLM and have grown with it. The best-known and now largest examples of this are PROCAD, with its headquarters in Karlsruhe, and CONTACT Software in Bremen.

A special role is played by ARAS, which seems to be in the running with the further development of a software originally developed by Eigner und Partner, the software company of the later Prof. Martin Eigner. The special role: Anyone can download the software free of charge; ARAS employees are paid for consulting services, which are then needed, as with other systems, to control processes in companies with it.

And finally, there were and are quite a number of system integrators who play a major role in connection with PLM for industry. After all, without their on-site help, many large-scale installations and system integrations would not have come about at all.

In Germany and in the German-speaking world in general, PLM is something special. I don’t know of any other region whose engineers and managers are so consistent in organizing their industrial processes. And for that, they need PLM. I suspect that this is an important one in a series of good reasons why German industry is still so strong. It contributes almost a quarter of the gross domestic product, and it provides the jobs for almost a quarter of all employees in Germany. The deindustrialization that has swept almost all other formerly leading industry countries, from Great Britain to France, Italy, and the USA, into its vortex, has so far been largely absent here. As far as I know, only Japan has experienced anything similar.

What is PLM?

As with all new terms, it was not easy to find out exactly what PLM meant in the first few years. But it had to be defined clearly, because after all, software licenses were to be sold to as many industrial companies as possible under this abbreviation. It had to be clear what PLM was all about.

The suppliers of industry software, especially in the area of product development, had their community of interest in Germany since 1995 in the sendler\circle – in the first years under the name CADcircle expertenforum. And there, for almost two years, a real fundamental debate took place on which definition at least the corresponding software providers could agree. Finally, in May 2004, this became the Liebensteiner Thesen, because the members of the sendler\circle had unanimously adopted them at a meeting in the Hotel Schloss Liebenstein.

The Liebenstein Theses are

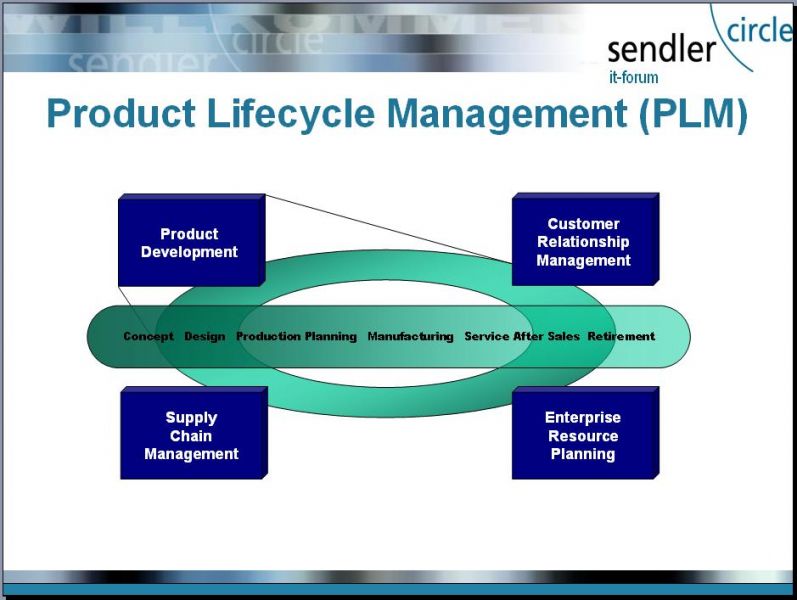

- Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) is a concept, not a system and not a (self-contained) solution.

- Solution components are needed to implement/realize a PLM concept. These include CAD, CAE, CAM, VR, PDM and other applications for the product development process.

- Interfaces to other application areas such as ERP, SCM or CRM are also components of a PLM concept.

- PLM providers offer components and/or services for the implementation of PLM concepts.

According to this definition, there should never have been a system called a PLM system. But then that was the case. In fact, there was soon a whole range of PLM systems for which their manufacturers claimed that they corresponded more or less extensively to the approach formulated in the Liebenstein theses. In practice, on closer inspection, this often turned out to be not quite in line with reality.

First, at the beginning, it was still mainly mechanical components and products that were covered by these systems, because the share of electronics and software only increased dramatically with the new millennium and soon led to concepts such as systems engineering and other methods of interdisciplinary collaboration in the development and manufacture of mechatronic devices. Consequently, it was somewhat presumptuous to assume that the first PLM systems could map the entire product development process of complex products and their lifecycle.

And secondly, these systems were mostly used in product development, and later also in production development. But to this day, it is only a small number of mostly larger companies that actually use the data managed in PLM for the other processes of value creation or even for the area of product operation or use up to recycling. After engineering, the availability of digital product models usually comes to an end. It is not uncommon for them to be recreated by other means in subsequent processes.

Nevertheless, at this point I would like to take up the cudgels for the original idea of PLM. When we talk about digital twins today, which allow the simulation of reality – for example, also of real products or their production facilities – then the basic prerequisite is usually that the data already created in engineering is recorded in its overall structure and managed centrally and cleanly, i.e. via PLM. In the very near future, this will be felt by all companies that, for reasons of cost, lack of personnel or other bottlenecks, have liked to regard PLM as something that is only interesting and necessary for the very large industries such as the automotive groups and aircraft manufacturers and their largest suppliers. It is necessary for everyone, regardless of size, who wants to use suitable digital twins of their products for new, digital services.

Why this series of articles?

As the founder and head of CADcircle and sendler\circle, I have experienced the development of these 20 years first hand, so to speak: I have seen the term and associated software systems come and go; I have seen how the vendors and their portfolios have evolved. Now I see how – following Autodesk several years ago – major PLM providers such as PTC and Dassault Systèmes are gradually leaving the circle and the community of interest and increasingly turning their attention to other topics. Although the topic of PLM is by no means finished and cannot be ticked off.

The fact that it continues to enable successful business – especially in the German-speaking region – is shown, for example, by the development of CONTACT Software and PROCAD, both of which now have around 250 employees.

This interesting mix gave me the idea for this background series. What exactly are the strategies that are hidden behind the market presence of the IT manufacturers (so far) known as PLM providers, which are so different from each other? What is changing for the user industry, what for the system integrators? What consequences does the emerging change possibly have for Germany or Central Europe as an industry location?

For this series, I have addressed: Autodesk, CONTACT Software, Dassault Systèmes, ECS Engineering Consulting & Solutions, PROCAD / Keytech, PROSTEP AG, PTC, SAP and Siemens Digital Industries Software.